The core purpose of CNC machining is to remove excess material from a workpiece, producing a part that precisely matches the specifications on the blueprint. However, achieving this in a single operation is nearly impossible. Multiple processes must be combined to progressively remove material layer by layer, such as turning, milling, face machining, drilling, slotting, and boring.

This process resembles a sculptor working with a block of rough marble. The artist would never begin by carving facial details with a small chisel. Instead, they would first use large chisels and a hammer to outline the figure’s general contours. This stage corresponds to rough machining in our machining process.

Once the fundamental form emerges, sculptors switch to increasingly fine chisels and sandpaper, meticulously refining the details through repeated polishing—this process is known as finishing.

What is rough machining in machining?

When you receive a raw blank for machining, rough machining is the first primary operation. Its task is straightforward: remove as much excess metal from the blank as possible in the shortest time, bringing the part’s shape and dimensions close to the drawing specifications. However, a certain amount of allowance must be retained.

Rough machining does not prioritize perfect surfaces or precise dimensions; instead, it places production efficiency first, aiming to maximize material removal rates.

Common Tools

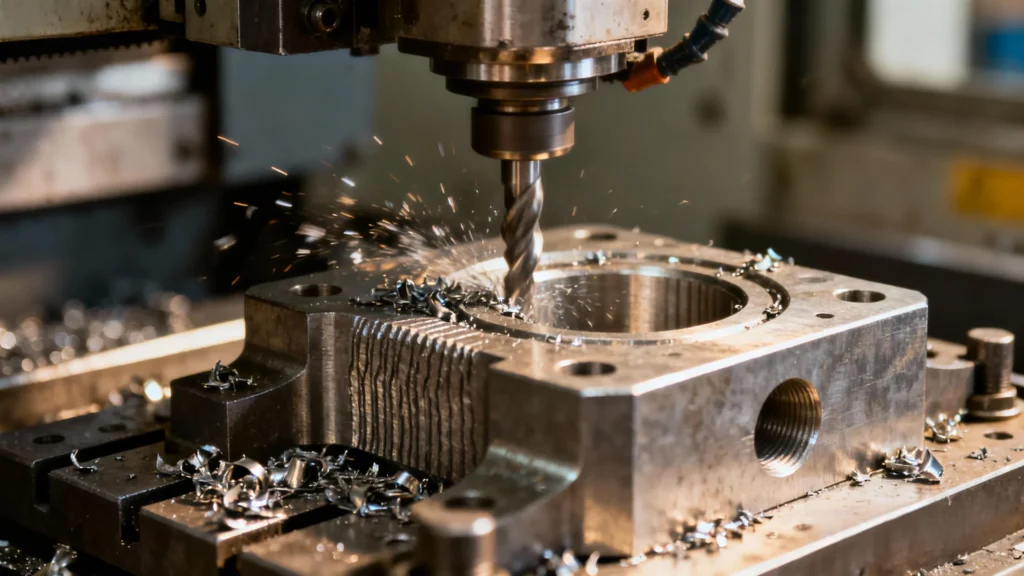

Roughing tools must withstand extremely high cutting forces, demanding exceptional strength and toughness. Below are commonly used tools for various machining methods.

| Machining Method | Common Roughing Tools | Characteristics |

| Turning | Roughing tool, external turning tool, chip-breaking tool | Robust cutting edge with large radius (0.8–2.0 mm), suitable for deep-cut machining |

| Milling | Roughing cutters, face milling cutters, circular insert milling cutters | Multi-edge design, strong chip evacuation capability, high feed rates; commonly uses carbide insert structures |

| Face machining | Face milling cutters | Large diameter, high rigidity, for rapid rough surface finishing |

| Drilling | Twist drills, carbide drills | Robust construction with large center angle, suitable for rough drilling of pilot holes |

| Slotting | Coarse-tooth end mills, keyway cutters | Fewer teeth and large chip pockets prevent chip clogging |

| Boring | Rough boring tools | Adjustable structure, large cutting depth, used for initial hole enlargement |

Below are examples of roughing tools.

| Workpiece Type | Recommended Tools | Tool Features |

| Steel | Round insert roughing end mills (R390, APKT series) | High chipping resistance |

| Aluminum Parts | PCD Face Milling Cutter | High-speed cutting, smooth surface finish |

| Cast iron parts | Ceramic inserts | Wear-resistant, thermal shock resistant |

| Stainless steel parts | Carbide turning tools | Anti-adhesion coating (TiAlN, AlCrN) |

Characteristics of Rough Machining

- High cutting depth (ap) and high feed rate (f): Each pass during rough machining rapidly removes a large amount of metal.

- Lower cutting speed (vc): This may seem counterintuitive, but to prevent rapid tool wear under the immense stresses of rough machining, spindle speed is typically reduced appropriately.

- Relatively relaxed cooling requirements: The primary objectives during rough machining are heat dissipation and chip evacuation, not achieving a perfect surface finish. Dry cutting can sometimes be employed.

- Machining allowance: This is critical. Rough machining must leave 0.5-2mm of material for subsequent finishing operations, allowing the finishing process to progressively refine the surface to perfection.

What is finishing in machining?

If rough machining gives a part its ‘form,’ then finish machining injects its ‘soul.’ The focus shifts from ‘efficiency’ to ‘quality.’

The ultimate goal of finishing is to achieve the final dimensions, geometric tolerances, and surface finish specified on the drawing. Dimensional accuracy is typically at the micrometer level.

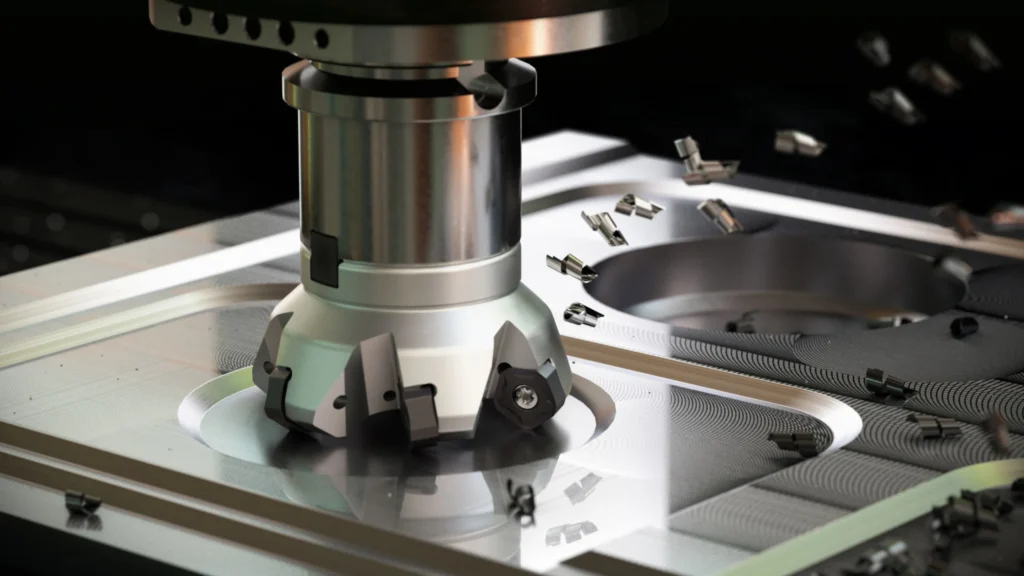

Common Cutting Tools

Below are commonly used tools for various machining processes.

| Machining Method | Common Tools for Finishing | Characteristics |

| Turning | Finishing tools, CBN inserts, PCD inserts | Small tool tip radius (0.2–0.4 mm) enables high mirror-finish precision; CBN suitable for hardened steel |

| Milling | Finishing end mills, round nose end mills, ball nose end mills | High tooth count and low runout for precision milling of curved surfaces or mold machining |

| Face Machining | Fine-finishing milling cutters, PCD tools | High-speed cutting achieves surface roughness Ra < 0.4μm |

| Drilling | Fine drilling, reaming | Improved hole accuracy and concentricity, with hole tolerances up to IT6 grade |

| Boring | Fine boring tools, micro-adjustable boring tools | Allows micro-adjustment of tool tip position, achieving hole accuracy up to ±0.002mm |

| Slotting | Precision grooving cutters, keyway milling cutters | Control groove width and positional accuracy to prevent secondary vibration marks |

Cutting tools used for machining objects

| Workpiece | Recommended Tools | Achievable Surface Roughness |

| Aluminum Alloy Mold | PCD ball-nose end mill | Ra 0.2 μm |

| Hardened steel (>HRC60) | CBN finishing tool | Ra 0.4 μm |

| Stainless Steel External Turning | TiAlN-coated carbide tool | Ra 0.6 μm |

| Fine Hole Machining | Fine boring bar + reamer | Ra 0.8 μm |

Characteristics of finishing processes

- Low cutting depth and low feed rate: Each pass during finishing removes only micrometer-level material; otherwise, part accuracy and surface quality will be compromised.

- High cutting speed: Combined with low feed rates, this enhances surface finish quality.

- Rigidity: The overall rigidity of the machine tool, cutting tool, and workholding (fixture) must be extremely high to prevent any minor vibrations that could compromise part accuracy.

- Cooling: Adequate cutting fluid is essential. It not only dissipates heat to prevent thermal deformation but also flushes away fine chips to avoid scratching the finished surface.

Differences Between Rough Machining and Finish Machining

Next, we will compare the main differences between rough machining and finish machining through the following five aspects.

Core Objectives

The core objective of rough machining is to remove material as quickly as possible, prioritizing machining efficiency. In contrast, the core objective of finish machining is to ensure the highest possible part accuracy and surface finish, prioritizing quality.

Machining Parameters

Rough machining parameters involve larger cutting volumes, high feed rates, and lower spindle speeds. Finishing operations employ the opposite approach: smaller cutting volumes, slow feed rates, and higher spindle speeds.

Tool Selection

Tools for rough machining must be robust and durable, with good impact resistance and a large cutting edge radius. Tools for finish machining, however, require sharpness, high precision, and a small cutting edge radius.

Machining Quality

Rough-machined parts exhibit coarse surfaces with visible tool marks and dimensional allowances; finished surfaces achieve excellent quality with precise dimensions meeting drawing specifications.

Cost Focus

Cost savings in rough machining primarily focus on reducing processing time per part. In contrast, finish machining aims to lower scrap rates, ensure product quality, and enhance product value.

Why Rough Machining and Finish Machining Are Both Essential

You might wonder: If finishing can produce the part directly, why add an extra rough machining step? Isn’t that a waste of time and increased cost?

My answer is: Without rough machining to “pave the way,” finishing operations would be “impossible to proceed”; without finishing to “put the finishing touches,” the part would be “unfit for purpose.”

Case Study

Take the engine cylinder liner we recently manufactured as an example to see how it transforms from raw material to finished product.

- Casting: First, the raw material is cast into the basic shape of the liner through the casting process.

- Rough Machining: The cast cylinder liner blank undergoes rapid turning on a lathe to shape the outer diameter and bore. This removes most of the machining allowance, leaving a rough surface approximately 1mm larger than the final dimensions.

- Heat Treatment: Stress relief annealing is performed to eliminate residual stresses from rough machining.

- Finishing: We place the cylinder liners on precision CNC lathes to finish-turn the outer diameter and bore with minimal cutting allowance, achieving the final dimensions specified in the drawings.

Making the Right Choice for Your Project

Now that you understand roughing and finishing theory, the next step is to learn how to apply these principles to guide your actual production.

When to Prioritize Rough Machining

When prioritizing machining efficiency and cost control, consider using rough machining. For example:

- Prototyping: When you need to quickly validate design concepts and surface quality is not a high priority.

- Large structural components: Such as machine tool beds, equipment frames, or non-mounting surfaces where material removal is the primary objective.

- First operation in high-volume production: This is the standard approach.

When to Prioritize Finishing

When high performance and reliability are critical for parts, you should prioritize finishing.

- High-fit holes and shafts: Such as bearings or pin holes where dimensional deviations of just a few microns can cause misalignment or excessive looseness.

- Dynamic sealing surfaces: Such as the inner walls of hydraulic cylinders or the sealing surfaces of pump shafts, where surface roughness directly determines oil leakage.

- Aerospace and medical device components: Parts used in these fields require extreme precision, fatigue resistance, reliability, and cleanliness.

Common Misconceptions

Skipping rough machining and proceeding directly to finish machining is an extremely costly and dangerous mistake. It leads to severe consequences:

- Finishing tools cannot withstand high cutting forces, causing tool breakage.

- Impact damage to the spindle and guideways, potentially causing machine tool damage.

- Part surfaces develop chatter marks, resulting in a finish worse than that achieved during rough machining.

Summary

Rough machining and finish machining are not mutually exclusive; they are complementary, indispensable partners in the machining process. Together, they form the complete chain of machining operations—one pursuing “macro efficiency,” the other pursuing “micro quality.”

Finding the perfect balance between them and maximizing their respective roles can significantly reduce costs, enhance production efficiency, and improve product quality.

We hope this article provides a thorough understanding of this fundamental yet critical concept in machining, offering valuable insights for your design and production practices.

About EVERGREEN Machinery

If you’re seeking a machining supplier, contact EVERGREEN. We are a mechanical parts manufacturer integrating casting, forging, sheet metal fabrication, and precision machining.

Here you can expect premium service, high-quality products, and professional technical solutions.